The new working class and the Pope's duty to be an "advocate of the poor"

By Andrea Tornielli

contains prophetic words regarding those people whom the author’s successor, Pope Francis, today calls “the discarded”. It is a realistic analysis regarding the major imbalances and the consequences of the exodus toward the large urban centers. It criticizes Marxist ideology and its atheistic materialism, but also takes to task that liberal ideology that would prevail less than twenty years later, thus definitively opening the way toward turbo-capitalism.

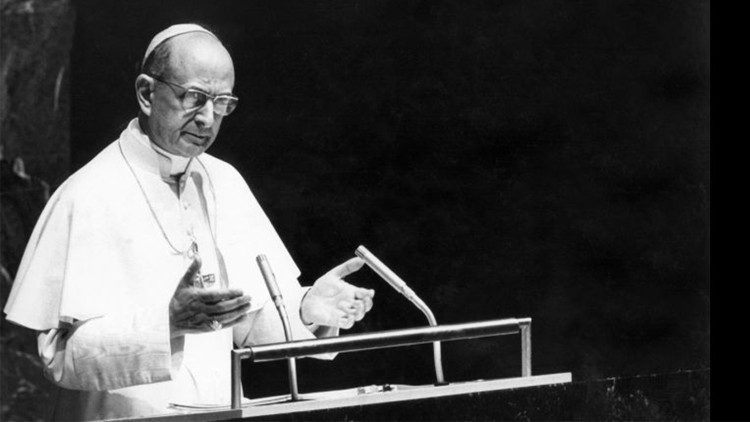

The year 1971 was running its course when on 14 May, Pope Paul VI recalled the eightieth anniversary of Pope Leo XIII’s with an apostolic letter addressed to Cardinal Maurice Roy, the Archbishop of Quebec and President of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace. The papal document — which covers poverty, development and political obligations — should be read through the lens of (1967), but also in light of the changes that had taken place in the years preceding it.

The Pope speaks of “flagrant inequalities” that “exist in the economic, cultural and political development of the nations”, citing the populations fighting hunger. He says plans of action, the obligation of concrete intervention, had to be left up to the judgment of each single local situation, because “it is up to the Christian communities to analyze with objectivity the situation which is proper to their own country, to shed on it the light of the Gospel's unalterable words and to draw principles of reflection, norms of judgment and directives for action from the social teaching of the Church”.

He thus draws attention to an important phenomenon that characterized both developed and developing nations: urbanization and the exodus from rural areas toward the metropolises. “In this disordered growth, new proletariats are born. […] Instead of favoring fraternal encounter and mutual aid, the city fosters discrimination and also indifference. It lends itself to new forms of exploitation and of domination whereby some people in speculating on the needs of others derive inadmissible profits. Behind the facades much misery is hidden, unsuspected even by the closest neighbors”.

Paul VI had become aware of the problems of the new peripheries of Milan while he was archbishop during the economic boom. As Pope, he continued to follow attentively the development of the Roman peripheries and to provide concrete help; financing the construction of 99 apartments, for example, in the part of Rome known as Acilia, destined as a housing development for the city’s poor. He wrote: “There is an urgent need to remake at the level of the street, of the neighborhood or of the great agglomerative dwellings the social fabric whereby man may be able to develop the needs of his personality. Centers of special interest and of culture must be created or developed at the community and parish levels”.

There is also a passage in the Letter dedicated to women. Pope Paul VI, who had proclaimed two women Doctors of the Church the preceding year – St Teresa of Avila and St Catherine of Siena – asks that discrimination toward them cease, and that legislation might “be directed to protecting her proper vocation and at the same time recognizing her independence as a person, and her equal rights to participate in cultural, economic, social and political life”.

Referring to the demographic growth in poor countries, Pope Paul defines as “disturbing” that “kind of fatalism which is gaining hold even on people in positions of responsibility” and “sometimes leads to Malthusian solutions inculcated by active propaganda for contraception and abortion”. The Pontiff speaks also of the environment and warns that through “an ill-considered exploitation of nature”, we “risk destroying it and becoming in our turn the victim of this degradation”.

Speaking of social and political obligations, Paul VI invites Christians not to adhere to “ideological systems which radically or substantially go against his faith and his concept of man. He cannot adhere to the Marxist ideology, to its atheistic materialism, to its dialectic of violence and to the way it absorbs individual freedom in the collectivity, at the same time denying all transcendence to man and his personal and collective history; nor can he adhere to the liberal ideology which believes it exalts individual freedom by withdrawing it from every limitation, by stimulating it through exclusive seeking of interest and power”.

Lastly, in what may be the document’s most memorable passage, the Pope expresses himself in favor of a plurality of political options for Christians, without comprising his or her adherence to Gospel principles: “In concrete situations, and taking account of solidarity in each person's life, one must recognize a legitimate variety of possible options. The same Christian faith can lead to different commitments”.

On Sunday, 16 May, two days after the publication of Octogesima adveniens, Pope Paul VI presided over Mass in Saint Peter’s to celebrate the anniversary of Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical, defining the words of his predecessor as “freeing and prophetic”. His homily became an opportunity for him to explain the motivation behind the Church’s social teaching: “Why did the Pope speak? Did he have the right to speak out? Did he have the competence? Yes, we respond, for he had the duty. Here, it is a question of justifying that intervention of the Church and the Pope on social questions, which, by their nature, are temporal matters, matters of this earth, which would seem to be outside the competence of those who draw their reason for being from Christ, who declared that His reign did not belong to this world”.

But, “looking closer”, Paul VI continued, “this Pope was not speaking about the kingdom of this world, or simply about politics or the economy. He was talking about the people who make up this kingdom, he was providing the criteria for wisdom and justice that must also inspire it. And under this aspect, the Pope’s voice, becoming an advocate for the poor forced to remain poor in the process of generating new wealth, becoming an advocate for the humble and exploited, was nothing other than an echo of Christ’s voice who made Himself the center for all those who are troubled and oppressed so as to console and redeem them; and who wanted to proclaim as blessed the poor and those who hunger for justice, and who also willed to be personified in every human being, small, weak, suffering, wretched, by taking on Himself the debt of an immeasurable recompense for anyone who had the heart and remedy for any type of human misery”.

The Bishop of Rome added that from this derives, “a right-duty of the Pope, as the representative of Christ and the entire Church, which is truly the Mystical Body of Christ, and of every authentic Christian, a declared brother to every other person, to be concerned, to care for the good of his neighbor; this right-duty is the strongest when the condition of the neighbor in need is more urgent, serious and pitiful”.

“And I would also like to say”, Pope Paul VI concluded, “that the Church in her ministers and in her members, is by her original vocation the ally of indigent and tried humanity, for her mission is the salvation of all, and because everyone is in need of being saved. But her preference is for those who are in need, even in temporal aspects, to be helped and defended. Human need is the primary title of her love”.

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here