Laudato si’: A priest’s commitment against uncontrolled urban development

Giada Aquilino - Vatican City

“Father, you take care of souls”. This is the phrase that Father Rosario Lo Bello has heard repeatedly since 2009 when he became pastor of the Saint Paul the Apostle Parish in Syracuse and began to carry out his pastoral and social ministry of what he calls a “reaffirmation of the public spaces” of the city, through raising awareness, empowerment and studying the landscape. Supporting him are a thousand parishioners from the Graziella neighborhood on the island of Ortigia. Only fishermen once frequented this island. Now it is shrouded in poverty, degradation and drug dealing. It is a raging river, Father Rosario tells Pope, while recounting his own dedication renewed each day, in defense of its panoramic, environmental and natural rights. Betraying a sense of relief, he confesses that in recent years he has found a type of “legitimization” in Laudato si’ by Pope Francis.

Contrast between modernity and backwardness

“After the war, in the ’50s”, he explains, this area “underwent considerable industrial development” in the name of “modernity” that entered the internal fabric of that part of Sicilian society “in a highly invasive manner.” However, this modernity did not keep with “true and proper social development”. The young, 45-year-old pastor from Syracuse, with a doctorate in Dogmatic Theology from the Pontifical Theological Faculty of Palermo, and former member of a group of researchers on the History of Medieval Philosophy at Naple’s L’Orientale University, who currently teaches History of Theology at Saint Paul’s in Catania, speaks about the local industrial zone – mostly oil and metalworking – as a source of “wealth” for the inhabitants over the years. Prior to the pandemic, he says, these two industries generated the only dependable wages in the city. That reality, he adds, always existed side by side a “context of backwardness, both from the cultural, civil and political perspectives”.

According to Father Rosario, “The middle-class sector in Syracuse was never forward-thinking. Even Christians engaged in social reflection”, he affirms, “often preferred to take refuge in abstract scholarship that helped foster a set of leaders largely devoid of cultural and social history. It is a bit like what all Sicilian cities were like in the ’60s and ’70s – businessmen and real-estate owners – who accumulated a certain amount of wealth. What impresses me is that today in Syracuse there are very few libraries”, he observes, “in comparison with the number of inhabitants” – over 100 thousand. In addition, the city is “constantly losing the young because there is no university. They prefer to attend universities in northern Italy”.

It is, therefore, a city of “adolescents, adults, the elderly, but those between 20 and 40 years of age are missing.” Unfortunately, he points out, “the steady increase in wages slowed little by little, especially in the last few years, causing a lot of poverty with no future in sight. I realize as a pastor, that many young people whose parents are unemployed do not have the possibility to study. They do not have access to enough bandwidth to take classes online, nor do they have money for books”. The coronavirus crisis aggravates such difficulties, especially for those working “under the table” who have no “pension and cannot request unemployment benefits”.

A protected marina

At the end of the ’90s, Father Rosario continues, “when it was obvious that industrial activity was slowing down, people lost jobs and the negative effects of industrial emissions began to be noticed on the health of the inhabitants. So, a second mirage for Syracuse was born: tourism – a tourism that was obviously anchored in positive values, for example, that of recovering and using archeological and architectural assets”. This plan, however, was characterized by “poor planning throughout the territory”. The priest cites the Regulatory Plans of 2005: “through a vast array of variants”, it opened the way to the “total urbanization” of the territory which then “made it more attractive to national and international investment”.

The city, he says, “expanded in a monstrous way” with the creation of new neighborhoods “that remained disconnected” from the others. “Particularly in the open areas in the south of Syracuse there was the possibility of constructing six resorts, all of which could host a high volume of potential tourists”, along the coast “where urbanization had not been strong”. Over the years, Father Rosario explains, two were completed: “the Fanusa and the Arenella”. Land had been selected for the others, including along the Prillirina beachfront, “a stretch of the Plemmirio coastal area of the Maddalena Peninsula which is a protected marine area since 2009” whose praises were sung by Virgil in the Aeneid. Father Rosario continues saying all this generated a movement against overdevelopment. A “grassroots movement succeeded in blocking the construction of these resorts, finding in Saint Paul the Apostle parish a place for reflection on identity which brought together scouts and members of Catholic Action from Legambiente, Arci, Italia Nostra”.

He remembers one demonstration in which the parish symbolically dramatized “Syracuse’s funeral caged within a concrete shroud”, and another in which “we carried plants and small flowers to one of the city’s urban planning meetings as a provocation”.

For Father Lo Bello, “the Regulatory Plans do not represent an idea connected to the collective interest in the city’s territorial plan, but it is often an exchange mechanism meant to promote the interests of some to the detriment of the great majority of the city. Obviously, organized crime is no stranger to all of this”.

Shared spaces

“Our reflection started for two primary reasons, which we found confirmed in Laudato si’ ”, Father Rosario explains. The first is that “a panorama has a value that goes beyond the purposes for which it can be commercially exploited”. The second is that “within the city, there should be spaces in which nature cannot be touched by anyone. I am talking about spaces”, he emphasizes, “that must continue to be shared. This idea is very important for us believers because shared spaces are places where everyone can go, the rich and the poor, the young and those who are not so young. This is especially so regarding coastal areas. They are not places destined for only certain types of people, but are places shared by various age groups and classes, where everyone can go to the beach”. He underlines that the Pope, in paragraph 151 of his 2015 Encyclical, also stated how necessary it is to “protect those common areas, visual landmarks and urban landscapes which increase our sense of belonging, of rootedness, of ‘feeling at home’ within a city which includes us and brings us together”, urging that we “see the larger city as space to be shared with others”.

Retaliation and support

This pastor is dedicated to restoring the good that creation has to offer to be enjoyed freely for decades to come. Dark moments were not lacking in which he faced retaliation, threats and insinuations against him even on a personal level.

“At first it was very difficult. I suffered a lot”, Father Rosario confesses. “In the face of some threats, my mother, a very self-controlled woman, would cry”, he recounts with a touch of emotion. “But when Laudato si’ by Pope Francis appeared, it was as if all of us ‘misunderstood’ priests like myself found legitimization. Now people understand that, if a pastor wants to focus on the degradation of a city, on shared spaces and on the possibility that its panoramic and natural resources be not only in the hands of those who are well-off but also for the poorest, it is because he is following the Church’s social doctrine. So today, despite everything, it is easier to carry out this mission”.

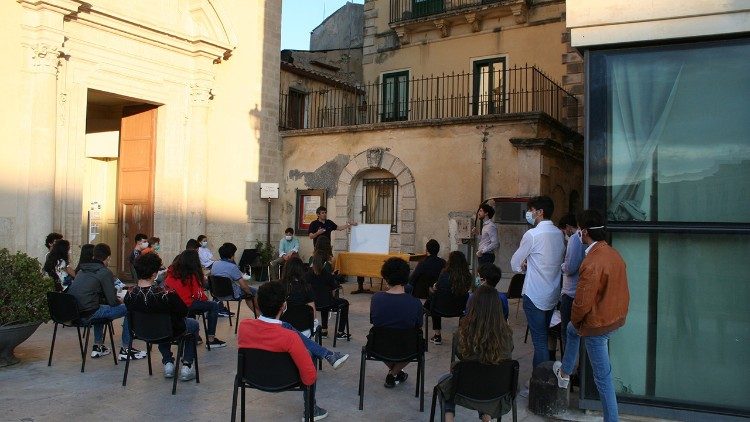

As if to reinforce his experience as a priest, he expresses this certainty: “I highly thank my community, especially my young people, because they are the ones who immediately perceived that the rumors they were circulating about me came from malicious sources, trumped up around the table, as the investigators later discovered. The young people in my parish, about twenty of them, have always supported me: I truly appreciate them”.

Future generations

To his parishioners of every age, Father Rosario continues to communicate the Pope’s invitation found in Laudato si’: that “we build together”.

“It is an act of love. Christ says: ‘love your neighbor as yourself’ and our neighbors are the children of these people or those who will be their grandchildren. To love your neighbor also means to leave behind a healthy environment and land to those who come after us. So, the idea that we must respect our planet in order to hand it on to the next generations, comes under Christ’s commandment”.

In addition, both Father Rosario and the parish’s young people have joined Jesuit Father Francesco Occhetta’s initiative called “Connected Community. “We are working on a political and social analysis of the city, taking inspiration from Laudato si’, and inviting feedback from the parish. Unfortunately, politics in Syracuse often continue to be uninterested in urban and environmental problems. We are aware that it is not enough to direct people toward a certain path, but that we must support them as well. For this reason, we hope to create soon a school to provide education to help those who have dropped out of school – there is a drop-out rate of 11% in Syracuse – to reintegrate them into academic and scholastic programs, even through various types of tutoring”.

This means that the journey of Saint Paul the Apostle parish in Syracuse does not stop here.

Thank you for reading our article. You can keep up-to-date by subscribing to our daily newsletter. Just click here